A brief history of Narrative Portraits

Nude portraits

Narrative portraits date back to Greece. Nobels would commission status depicted of themselves as educated scholars, warrior type figures, athletes or paying homage to mythological figures. Typicaly idealised in the nude or some state of undress. The culture celebrated the human form as a higher aesthetic, unlike the Western culture of today which is generaly inhibited by nudity in art.

Donor portraits

Most medieval portraits were donor portraits. They are common in religious works of art, especially the paintings of the Middle Ages through to the Renaissance. The donor is usually shown kneeling to one side, in the foreground of the image and, late into the Renaissance, the whole family could be shown. By the mid 15th century donors were shown integrated into the main scene, as bystanders and even participants.

As an example patrons commissioning a Fresco for a church would have themselves painted into a religious scene, with a hierarchy of those donating the most being the most prominent in the Fresco. The Medici family who almost bankrolled the Renaissance are to be found in various Fresco scenes in churches throughout Florence.

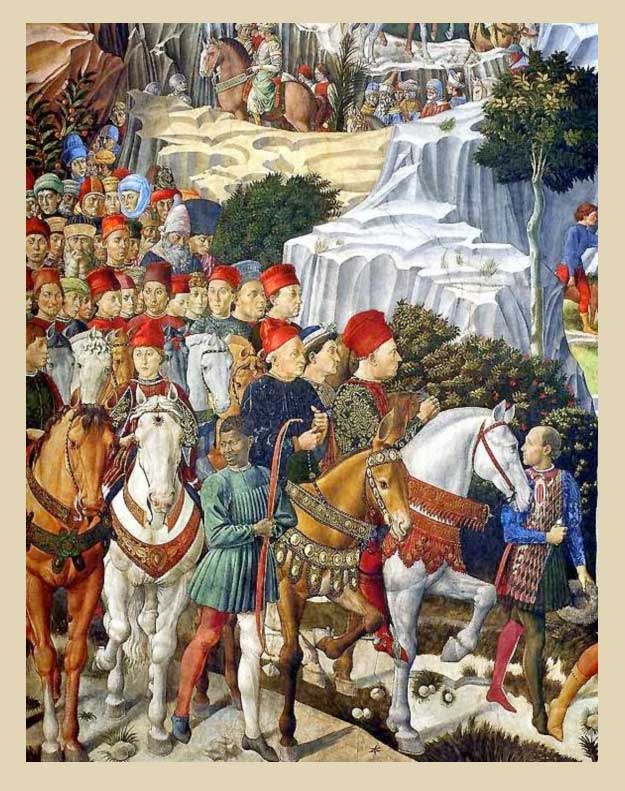

Detail from the Magi Chapel at the Palazzo Medici in Florence.

The above shows a Fresco depicting The Procession of The Magi (1459-1460). (The journey of the Three wise men to Bethlehem).

The Fresco promotes Cosimo de’ Medici, Lorenzo Medici and other prominent Italians. The religious theme was a pretext to show the procession of important people who travelled to the meeting of the Council of Florence (1438-1439). The Fresco is probably the Medici’s boasting about their part in the reconciliation between the Catholic and the Byzantine churches.

Themed portraits

The themed portrait is recognised as becoming more popular in later years. Painters would paint their subjects in period costume or introduce some historical theme so the painting would not appear to date as contemporary fashions change all the time. Rembrant was such an artist dressing many of his patrons in styles and themes 100 years or more.

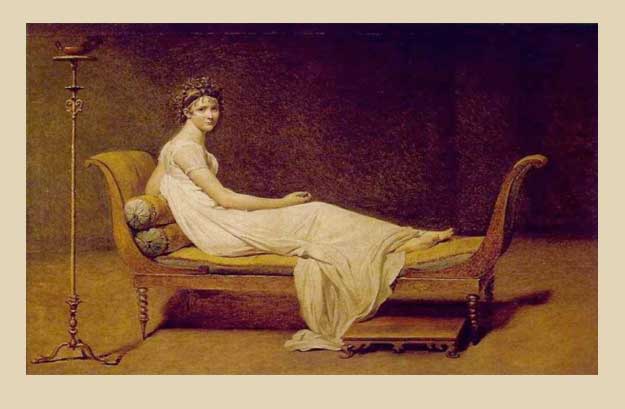

This tradition has continued through the ages, below is ‘Portrait of Madame Recamier’ an 1800 portrait of Juliette Récamier by Jacques Louis David, showing her reclining on an empire style sofa, in an empire line dressed as a modern vestal virgin.

Jacques-Louis David, portrait of Madame Récamier (1800), Musée du Louvre, Paris

Why a narrative portrait?

Narrative painting is a style that I would like to specialise in the future, having the sitter as a subject in their own theatrical composition. Inspired by tales from legends, myths or actual events in history. Creating a a larger than life view of ourself that we can aspire to.

Most stories from Ancient history and religion are a moral guide through our experience of the human condition. Usually dark tales with the hero triumphing over adversity.

We all identify with the parts characters have played in these dramas. I would like to paint narratives that are personal affirmation of those experiences.

For example, the portrait of Holly is based on the story of Prometheus.

He was a champion of mankind who stole fire from Zeus and gave it to mortals. Zeus punished him for his crime by having him bound to a rock, while a great eagle ate his liver every day only to have it grow back, to be eaten again the next day. Holly is looking into the face of the eagle with a calm resilience, accepting the fate that lies before her. The scene is positive affirmation of endurance, the courage and perseverance to face the suffering of everyday life.

This genre of painting could be considered as being egotistical, or self centred but patrons didn’t seem to have a problem in the past.